Elmfield College

A snap-shot of life at the school in 1912

Transcription of an Article in the Christian Messenger in the series “Some of our Workshops” by “An Admirer”

EMFIELD COLLEGE is pleasantly situated on the main road about a mile from the historic city of York. The visitor has no difficulty in finding the College; he only requires to ask when he leaves the railway station, “Where is Elmfield?” and any resident in the Minster city will be delighted to give him the necessary information. The view from the turnpike, as one approaches the famous educational centre on a time spring morning, creates the impression that it is an ideal place for boys, which is confirmed by the healthy and vigorous appearance of the eighty lads who are in residence and training for the great work of life. Their obvious physical resources are an excellent testimony to the roominess, the diet and the management of the college. Those who have been in residence a year or two seem capable of bearing almost any tax upon their strength in subsequent years.

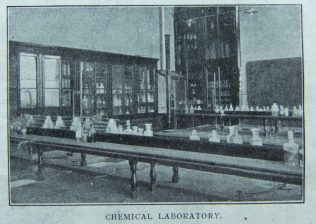

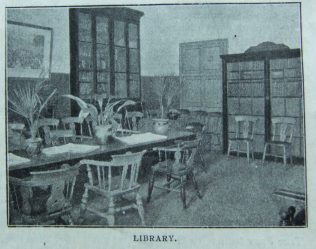

Everything has been done to give the school a commanding place among similar institutions in the Country. A first-class physics laboratory, a manual workshop, a laundry, and other minor improvements have been added during recent years at a cost of £1,200 There is a splendid technical staff of “degree men,” and the efficient working of the College is guaranteed by the devotion of the secretary Mr. C.C. Hartley, and especially by the tactful government of the headmaster, Mr. S.R. Slack, B.A. The latter is to the manner born. Nature has been kind to him in the provision of build and buoyancy to enable him to inspire and manage boys. No mother could desire for her son a finer influence in directing and educating his youthful energy and endowments.

But I began this article with the intention of describing a day among the boys, and a fear of editorial impatience and the urgency of the reader compels me to begin. What a task! If it is difficult to sketch the life of a single child, the difficulty is increased immensely, when the subject deals with a day in the life of eighty lads, ranging in age from ten to seventeen or eighteen years. They are what Mrs, Browning would describe as “aspectable.” Their moods, habits, tastes, studies, pleasures; their aversion to programme and discipline until time and influences have broken them in; their receipt and despatch of correspondence; their natural and unnatural saintliness ; their moral estimates of men and things, their expanding energies; their world of romance and castles, their preferences and prejudices – these and sundry other aspects too numerous to mention enter into their life and work-a-day world of experience. A complete account of a day in the life of these lads would have to find room for these and other real, but elusive, factors. Such a task is beyond the power of pen, or, in the case of fortunate beings, typewriter; and it is a comfortable thought that a considerate editor does not expect more than moderate success in such an enterprise.

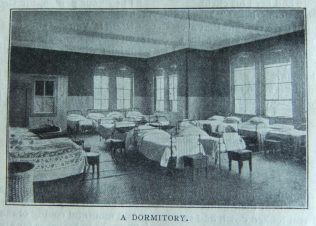

But I must get on. There are eighty boys in residence. They rise in summer at six o’clock, and in the winter a little before seven o’clock. You may be quite sure that the bed frequently pulls, and, sometimes, the toilet processes are gone through in an inconceivably brief period. Those who require a recipe to prevent delay between rising and thinking should consult some of these boys. From seven to eight they are busy with preparation work, for time is necessary for independent effort as well as tutorial oversight. They have breakfast at eight. Here, usually, there are no late arrivals. The calls of the stomach guarantee punctuality and ample consumption.

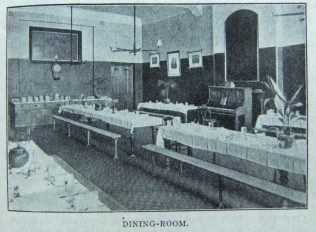

By a swift process of transition they pass from the material to the spiritual. Morning worship immediately follows breakfast. The service is simple and beautiful, consisting of Bible reading, singing, and prayer by the headmaster. The boys assemble for school-session at nine, and, after the roll-call, pass to their class-rooms, where the educational foundation for future usefulness is being well and truly laid. With the exception of a brief interval, lessons are given till half-past twelve, when dinner and the expectant juveniles are both “ready.” It is a tribute to their capacity for the perishable things of life that, while at play there is an incessant flow of original oratory, they are able to maintain a voluntary silence when at meals. After dinner they have a few minutes for open-air exercise; they assemble for the afternoon session at half-past one, and continue lessons for two hours. On Wednesday and Saturday afternoons, however, they have a half-holiday.

The afternoon hours for recreation are always wisely spent, and care is exercised in the arrangements to meet the divergent tastes of boys. After session they are at liberty to go for walks or cycling runs, but they are expected to return not later than a quarter to five. During this bipedal or cycling are not under the eye of a tutorial policeman; they are, however, expected to maintain the honour and reputation of the school, and wear the school cap. This head-gear preserves them from riotous living. Only one condition is attached to the rambles and rides. They must go into the country. They are not allowed in the city, except to meet friends. These sane regulations act in the way of a beneficent compulsion, for a boy must be governed without feeling a sense of severity, and usually does best when he knows that he is trusted.

Those who do not go for rural exercise play at cricket in the summer and football in the winter. The school is divided into teams, and in football especially, great efforts are made by each team to “head the league.” The medals, which are presented to the winners at the end of the season, are a coveted prize. On Wednesday and Saturday afternoons matches are played with the other schools and colleges, and “our fellows” manage to hold their own. In fact, “Elmfield” has earned the right to be respected by any team in the district. These athletic achievements are full of romance, and, in the estimation of the youngsters, of unspeakable significance.

Tea is at five o’clock and, after tea, the boys of the junior forms engage in gardening until seven. Each has his plot of ground, and is taught by one of the masters the scientific methods of growth, and the thousand and one things which belong to scientific gardening. The boys take a perfect delight in their task, which obviously forms one of the healthiest and most valuable departments of their studies. Then from seven to eight all are engaged in preparation work. The juniors retire to bed fifteen minutes after the latter hour, the seniors at nine o’clock. .

A few matters of interest demand special notice. The “prefect system” is worked with beneficial results. The senior boys are allotted certain responsibilities in looking after the interests of the juniors. This sense of responsibility steadies a youth, for at sixteen years of age his future is being shaped. He may become either a man or a hooligan. His feeling that the welfare of the school partly depends upon him gives him a new and maturer outlook, and the privileges attached to his position he duly appreciates. The head-master is just the man to turn to excellent account the advantages of the “prefect system.”

The religious education of the boys receives due attention. They, attend the Monkgate Church on Sundays. On Tuesday evenings a Christian Endeavour meeting and a preaching service are held alternately, conducted by the Circuit ministers, who rightly regard this work as of the utmost importance. Magic lantern lectures of scientific and general interest are frequently given, and debates on topics of living interest are held. Recently a debate on conscription took place, and resulted in a vote against it. The leader in favour of it nearly won the minds of his student audience by the use of an argument which naturally appealed to boys. He held that the opponents of the proposal were guilty of cowardice. He evidently knew how to appeal to the pugilistic instincts of youth.

One may be sure that dull routine is an impossibility in a boys’ school, and Elmfield is no exception. Humour abounds. During the school session a while ago, the master noticed a boy chewing. When he knew that his facial movements were under observation, he managed, by dexterous arrangements, to get the sweet from his mouth and put it on the hair at the back of his head. When the time came to remove the sweet it was found impossible until the hair was cut close to the scalp. The bald patch served for days to provide amusement to the juvenile lovers of fun.

The “howlers” are numerous. One boy said that the “Black Death” was so called after the death of the Black Prince. Another boy, asked what was the meaning of the Gallic Law, replied, “It was a law that said that nobody descended from a woman could inherit the French throne.” Humour sparkles in the pages of the Elmfieldian, a monthly paper published by the College. One of the numbers sometime ago published the questions and conditions of entry of a prize competition, arranged by “Diogenes.” Each competitor must forward a postal order for two shillings, and the answers must not exceed five thousand words in length. The questions were divided into an elementary and an advanced section. In the advanced section clearness of apprehension and style were expected. Candidates were also expected to read the questions after writing their answers. Among the questions were the following:

1. Describe the feelings of a “spanking” game.

2. What is a kid? When is it a “ goat”?

3. Explain with reference to the possible context: “Shut up,” “Nix,” “Go and eat grass,” “ Swank,” “Conservative,” “ Chuck it.”

4. Is it robbery to “take an hour”? Being taken, where should it be deposited?

5. What is the relation between Common Law, Jimmie Law, and Oh! Law?

6. If it has taken fourteen hours to set this paper, how long will it take you to answer it, having clearness of apprehension in all parts? Difference of faculty not to be counted. Extra marks if worked by decimal algebra.

This brief description of the life of Elmfield fails to do justice to the profound influence which it brings to bear upon the boys brought within its precincts. The days pass delightfully, and provide the years of manhood with memories which become idealised and potent. The College has filled an important place in the Church and in the preparation of men for public life. Happily the prospects are bright. No school could possess a better teaching staff and directorate. Mr. Dyson Mallinson has given enormous attention and generous thought to the interests of the institution, and he is ably supported by a splendid band of co-directors. Long may it stand to add illustrious names to the church and train men for the advance of civilization.

References

Christian Messenger 1912/200

No Comments

Add a comment about this page