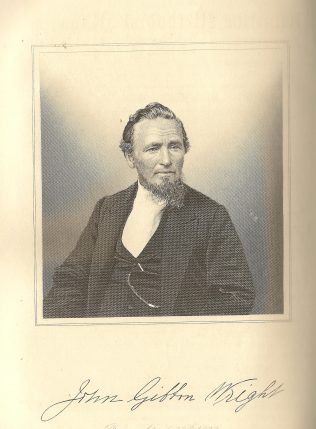

Wright, John Gibbon (1822-1904) : His Voyage to South Australia

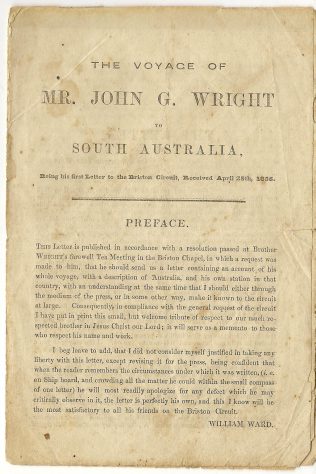

'Being his first Letter to the Briston Circuit, Received April 25th, 1856'

John Gibbon Wright (1822-1904) was born in Sculthorpe, Norfolk, and ended his life the other side of the world in Australia. The story of how he got there is told in a letter written to his friends in England.[1]

Early life

John was an agricultural labourer, but in 1845, at the age of 23, he became a Primitive Methodist minister. His first ‘station’ was in the North Walsham circuit.[2] The following year he was sent to Bury St Edmunds, and in 1848 to Wisbech in Cambridgeshire. It was here that he met and married Charlotte (neé Randall) in 1850.[3] The day after their wedding, as they walked along the river bank, the young couple set the pattern for their life together, resolving: never to go beyond their income; to pay for all goods when they received them; to give God a tenth of all they received; and always to put God first. They were to keep their resolutions for nearly 50 years.[4]

Offers as a Missionary

The young couple moved next to Swaffham, and then on to Briston, in Norfolk, in 1852. It was here that John decided to offer as a missionary for South Africa, as he had friends there. However, as Charlotte later recalled, much to their dismay, when their ‘moving orders’ arrived, they discovered they were to go to South Australia instead .[5]

There was an emotional farewell in Briston, where a Tea Meeting was held in the Chapel, and people begged John to write and tell them all about the voyage, Australia and his experiences ‘among the heathen’, as they were sure he was ‘in for rather an exciting time’.

It is interesting that when the letter arrived, William Ward, to whom it was sent, felt it necessary to apologise for its deficiencies, begging the reader to remember ‘the circumstances under which it was written’. Perhaps he felt that John should not have been so honest about his, sometimes very raw, emotions.

On Board the Ship Walvisch

‘To all the friends of Jesus on Briston Circuit[6] … Since I last saw you, weeks and months have now passed away, oceans now roll between us, and hills and mountains separate us far from each other, but neither time nor distance in the least impairs my affection for you … I felt I loved you, but never more than I do now’. John and Charlotte were homesick. Not only that, but they were dreadfully sea sick, and three days into the voyage, while the ship ‘began to reel like a drunken man’, Charlotte went into labour.

It was a Dutch ship, the only doctor on board spoke no English, and John was very afraid that Charlotte would die. With their two small daughters, Elizabeth and Mary, crying, and wanting to go home, John could only weep himself, and say to himself, ‘Hope thou in God’. After much prayer, a baby son, John George, made his appearance ‘in the English Channel, off DoverCastle’. The birth was followed by a period of unusual calm, which enabled Charlotte to get her strength back and the baby to thrive. John could now exclaim: ‘How good the Lord is to me!’.

Still they continued to miss their friends, and John mourned ‘the mouldering bones’ of his father, and his ‘dear, dear mother, whom my soul loveth, but to whom for Christ’s sake I have bid farewell’.

Sundays are my worst days

‘Sundays are my worst days, in the morning I preach, and in the afternoon the Dutch are dancing, swearing, and sometimes fighting, and on one Sabbath they got drunk, and three were stabbed by knives. We go down into our berth, read and sing, and call to mind past days’. John and Charlotte wonder if ‘poor Tubby is now going to chapel’, and ‘where friend Ward is today’. They wonder if ‘old friend Stimpson is still alive’, and whether Mrs Rudd ‘has gone home’, and remember Mrs Ward, ‘how sweetly should we enjoy a cup of her tea’.

A sublime scene

The ‘sublime sight’ of one of the Canary Islands, ‘its peak piercing the very clouds, which hung like silvery curtains around it, fringed with the brightness of the setting sun’, marked an upturn in their emotions. John still had to wash and dress the little girls, as Charlotte was too weak to stand, but by the time they were off the Cape of Good Hope she was better, and they started to enjoy themselves.

Finally, on 1 January 1856 they came in sight of Australia, ‘the sea placid and sparkling, the heavens of a deep sky blue …’, it was a ‘scene that affected my whole soul, and moved my heart to its very core’. They landed in Adelaide after a voyage lasting nearly four months, and on their first Sunday, the first person John saw when he went to preach at the Chapel was a man from the Briston circuit: Mr Nurse, from Kelling.

Adelaide was not John and Charlotte’s final destination. They still had 100 miles to go, deep into the bush, to reach the copper mines at Burra Burra, where John was stationed. As Charlotte later recalled, ‘We had a long, long, long way to walk.’[7]

The gold rush

A chapel had been opened in 1849, but the discovery of gold in Victoria the following year left the township of Kooringa deserted, and the chapel closed, its miners rushing to the gold fields.[8] In a report sent to the Primitive Methodist conference in 1856 there were only two members at the Burra – Mr and Mrs John G Wright![9]

Despite their initial misgivings, John and Charlotte threw themselves into the work. John began by preaching in the open air, and people flocked to hear ‘his magnificent voice’. He was not afraid to get his hands dirty, and even worked in the mines himself, raising the stone to rebuild the chapel. In 1857 there were 89 members, and by 1858 the number had increased to 114. This was partly due to some of the miners returning to Burra Burra from the gold fields, but even so, it shows the success of John’s ‘true apostolic zeal’, which led him far into the bush to minister to isolated colonists. He became their ‘beloved minister’, and Charlotte his ‘excellent wife’.[10]

Exciting times

John must have written many more letters back to Norfolk, telling them of his experiences, but they are yet to be discovered. He also kept a diary, which shows he did indeed have ‘exciting times’ in the rough mining community at Kooringa.

8 April 1856:

‘This has been a day of days. In the morning I was called to visit a poor man who had been for days under conviction of sin. When I entered the house he fell on his knees with horrific groans. For one hour he was in the greater agony. ‘I cannot live, I cannot live. I will not let thee go. I will believe.’ Soon he found Christ and began to sing ‘I never shall forget the day, When Jesus washed my sins away’.

24 July 1857:

‘Attended a prayer meeting at Kooringa. A man by the name of F Cock was brought to God. He had been notorious for crime, had took his wife by the hair of the head and swung her round the room. When made happy he ran round the house praising God. A poor man by the name of Jenkin had not long before got his jaw broken, he got so happy he praised the Lord shouting ‘I will praise the Lord, I will praise the Lord though I have a broken chack [cheek]’.[11]

A very happy experience

Despite hardships endured, John and Charlotte had another five children born in Australia, and lived to a good old age. Charlotte was something of a celebrity when she was interviewed by the local newspaper in Adelaide in 1915, at the age of 89. She sat with the Family Bible on her knee, recalling their experiences from their arrival on the ‘Walvisch’, concluding: ‘After the Burra we came to Adelaide. There was a nice little church in Waymouth Street, built in the old English style, with doors opening to your pews, and you buttoned them when you got in. From Adelaide we went to MountBarker, Salisbury, Strathalbyn – oh, many places I cannot remember now. It was all a very happy experience.[12]

[1] The Voyage of Mr John G Wright to South Australia, preface by William Ward, printed by J Colman, Holt (1856), 8 pp. [Englesea Brook Museum, PB.9]

[2] Methodist ministers are ‘stationed’ or sent to work in a circuit, which is a group of churches, or ‘societies’ in a particular area. The list of John’s stations in England and Australia can be found in W Leary, Directory of Primitive Methodist Ministers & their Circuits (1990)

[3] Charlotte was born in Suffolk in 1826, the daughter of Bloom and Elizabeth Randall. They provided hospitality for travelling preachers. In the 1841 census, two ‘Preachers’ were staying with the family.

[4] South Australian Register, 24 Jan 1920; www.ancestry.co.uk.

[5] ‘Her Ninetieth Year: chat with Mrs J G Wright’, South Australian Register, 11 Aug 1915; www.ancestry.co.uk.

[6] John sends his love ‘to all the dear people in Briston, Kelling, Cley, Salthouse, Langham, Foxley, Binham, Waybourn, Letheringsett, Fulmodeston, Sharrington, Edgefield, Glandford, Blakeney, Gunthorpe, Bale, Hindolveston, Guestwick, Holt, Thornage, Dalling and Hunworth’, showing which places were in the Briston circuit in 1855.

[7] ‘Her Ninetieth Year’, op cit.

[8] Many miners were Methodists from Cornwall. Local preachers in 1849 included Messrs Rowe, Symons, Hayes, Berryman, Prior, Scoble, Moyle and Nicholls; P Payton, The Cornish Overseas (2005), p.193.

[9] J Petty, The History of the Primitive Methodist Connexion (1880), p.528.

[10] ‘Her Ninetieth Year’ op cit; Primitive Methodist Magazine (1855), p51; Petty, op cit, p.528-9.

[11] Payton, op cit, p.195.

[12] ‘Her Ninetieth Year’ op cit; obituary of Rev J G Wright, Minutes of Primitive Methodist Conference (1905) p.48-9.

No Comments

Add a comment about this page