The Early Sunday Schools of Gloucester

A Primitive Methodist take on the development of the Sunday School Movement by Robert Raikes and Rev. Thomas Stock.

Transcription of Article in the Primitive Methodist Magazine by Rev. W.L. Taylor

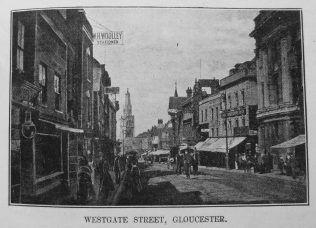

In view of our Triennial Sunday School Conference an article on the Gloucester schools may be of interest. Historic Gloucester, the “Glevum” of the Romans, is justly regarded as the Mecca of English Sunday Schools. True, there were isolated instances of Sunday Schools in the country before those founded by Robert Raikes and his fellow-enthusiast in this work, the Rev. Thomas Stock, in 1780; but, since a concrete expression was there given of the possibilities of reclamatory and educational work among the young, and an impetus created which nationalised the movement, it deserves the place of honour which by general consent is given to it. From a purely local movement, the Institution became national, largely through the journalistic influence of Raikes in the “Gloucester Journal,” of which paper he was the proprietor and editor. In the sense that he, by strenuous work in the two schools established in the city, and advocacy of the movement in the columns of his newspaper, set people talking of the work, and spreading its beneficent influence, posterity well acclaims him as the human founder of this great Institution.

Among earlier instances, it is known that at Ashbury, Berks, there was a Sunday School founded by the clergyman of the parish, the Rev. Thomas Stock, who afterwards became the Rector of St. John’s, Gloucester, and the noted yokefellow of Raikes in this Christian and philanthropic work. Also, at High Wycombe, Bucks, Miss Hannah Ball, a young Methodist lady, had gathered the children together for religious instruction in 1769, eleven years before the first Gloucester Sunday School: surely, an impulse and expression of the new philanthropy born of the great Methodist Revival. So, the historian, Mr. J.R. Green, thinks and says.

In a letter written by Miss Ball to John Wesley on December 16th, 1770, there is this reference to this early school: “The children meet twice a week, every Sunday and Monday. They are a wild little company, but seem willing to be instructed. I labour among them, earnestly desiring to promote the interests of the Church of Christ.”

At the Centenary celebration of the origin of Sunday Schools in the country, in 1880, in this town a banner was carried in the procession bearing the inscription, “Wesleyan Methodist Sunday School, Founded 1769.”

The part which Raikes took in the work is now well-known. On the marble slab in St. Mary de Crypt Church, Southgate Street, Gloucester, above his grave, next to the graves of his parents, may be read this tribute in Latin: “Also of Robert, their eldest son, by whom Sabbath Schools were first instituted in this place, and were also by his successful exertions and assiduity recommended to others. He died on the 5thday of April, in the year of our salvation, 1811, in the year of his age, seventy-five.”

So, silently, the marble gives out its message in honour of the man who is well entitled to be called the children’s friend. It will be noted that personal example and advocacy of the work are given as his honours. George the Third, who said in relation to the Lancastrian Day Schools, soon afterwards formed, “It is my wish that every poor child in my dominions should be taught to read the Bible,” with Queen Charlotte, evinced great interest in the Gloucester schools for boys and girls.

Scanning thefacsimilecopy of the “Gloucester Journal” for November 3rd, 1783, we see the first public reference to this movement, in the following terms:

“Some of the clergy in different parts of the county, bent upon attempting a reform among the children of the lower class, are establishing Sunday Schools for rendering the Lord’s Day subservient to the ends of instruction which has hitherto been prostituted to bad purposes. Farmers, and other inhabitants of the towns and villages, complain that they receive more injury in their property on the Sabbath than all the week besides: this in a great measure proceeds from the lawless state of the younger class, who are allowed to run wild on that day, free from every restraint. To remedy this evil, persons duly qualified are employed to instruct those who cannot read, and those that may have learnt to read are taught the catechism, and conducted to Church. By thus keeping their minds engaged the day passes profitably and not disagreeably. In those parishes where this plan has been adopted, we are assured, that the behaviour of the children is greatly civilised. The barbarous ignorance in which they had before lived, being in some degree dispelled, they begin to give proofs that those persons are mistaken, who consider the lower orders of mankind as incapable of improvement, and therefore think an attempt to reclaim them impracticable, or at least not worth the trouble.”

It will be seen that no mention is made of Raikes himself; surely an evidence of the simplicity and quiet goodness of the man.

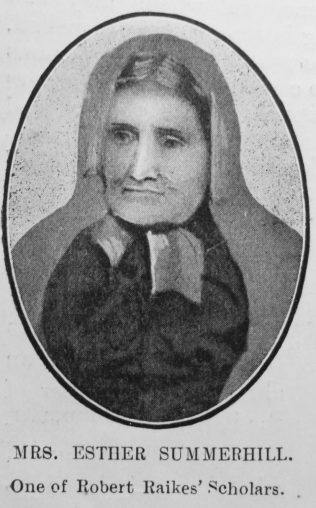

In 1881, there was living at Gloucester an old lady, a member of the Barton Street Primitive Methodist Church, who was privileged to be one of the scholars in the school for girls started by Raikes in 1780. Her name was Esther Summerhill. Gladly did she give to the travelling preacher who visited her, particulars of the general methods of conducting those early schools, and justified the record some faithful “Boswell” has made that it was the habit of Mr. Raikes to reward regular attendance and good behaviour with such trifles as cakes and pennies. Mrs. Summerhill, whose picture we are able to give with this article, had a place of honour in the great Centenary procession in Gloucester city in 1880. Another old scholar was with her in the person of Mr. James Woodward. Both have since then ‘‘passed on.” From these authentic accounts of the early work we see that a charity idea largely pervaded the minds of the first workers in this sphere, the ragged school institution being a bye product.

It is generally conceded that in his visits to Gloucester Castle, where the felons of that day were confined, Raikes saw the necessity for a proper training of youth. Crime, the handmaid of ignorance, was then very prevalent, and the repressive statutes of the period were found insufficient to deal with it.

It is a sign of the moral advance which England has made that a spirit of humanity has taken possession of the nation, and that now all condemn many of the punishments of those days as excessive, demoralising, and cruel. In the same copy of the newspaper in which reference was first made to Sunday School work, we see an account by the penny-a-liner of that day, of the public executions at Tyburn, which, only to quote, is evidence of the barbarous spirit then dominant, in the punishments inflicted for theft.

Here it is:

“This morning the following malefactors were conveyed to Tyburn attended by the two sheriffs, the under sheriffs, city marshall, and other officers, viz., John Burton and Thomas Duxson, for a burglary, James Neal, for stealing a quantity of plate; John Booker for robbing on the highway, Thomas Smith and John Starkey for stealing two bank notes, value £25, and £8 in money, William Moore for coining shillings, the last-named being drawn on a sledge. They all behaved very penitent.”

The experience gained by Raikes in such prison associations was doubtless the inspiration to his work in the religious and moral interests of the young. He learned the direct connection between ignorance and crime, and saw the futility of punishing the effect without attempting to remove the cause. At the same time, his prison philanthropy probably explains the charity conception of the Sunday School which prevailed at the time, and which finds a place in some degree, in these enlightened times.

It is the keen regret of religious educationists to-day that the standard of duty and service is so low, though every attempt is being made to give teachers a higher conception of their work. In a measure we are handicapped by the prevalent notion at the beginning of the Sunday School era that such work was supremely if not exclusively suitable for the children of the poorest and most degraded of our country. A true vision will lead us to call for the service of the most cultured and Christian of our workers in this important ministry of the Church today. We are told that the record of American schools is different; that the highest talent and ability of the leaders of the Church of Christ are there laid upon the altar of Sunday School service. It ought not to be very long before England learns the lesson, and sees the immense possibilities bound up with this Institution.

The progress in Sunday School Reform, though slow, shows the trend of thought, and forecasts the predominant note in future days. Till that happy time dawns, we thank God for what has been done in the early Sunday Schools of Gloucester, and since.

James Montgomery, who was privileged to see the rapid spread of this beneficent movement, phrased its glorious progress thus:

“Once by the river side

A little fountain rose;

Now like the Severn’s seaward tide

Round the broad world it flows.”

References

Primitive Methodist Magazine 1907/808

No Comments

Add a comment about this page