Aliwal North

Mission Work in the Land of Good Hope

Note: This historical article reflects colonial attitudes that we are not comfortable with in modern times.

Transcription of Article in the Christian Messenger by Rev. George Ayre

THERE are many distinctive features in the Christian work amongst the natives of South Africa which immediately strike the newcomer as novel and interesting. Those who work in these fields become so used to these things that the element of surprise vanishes, and we sometimes overlook the fact that things which have become quite usual and commonplace may be of striking interest to those who view the mission field for the first time. Let us try to view matters through the eyes of a stranger. Probably the first things to strike one in approaching a native church at the time of service would be the novel method of calling the worshippers together. Most of our town churches are the proud possessors of a bell, the ringing of which is one of the honours to which our members aspire, and in the out-stations, bells not being easily procured, the call to service is made by all manner of ingenious gongs. At one place we have an old piece of locomotive rail hung on a tree and beaten with a rod of iron. In another it is an old plowshare which the steward beats with the key of the church, and elsewhere an old shell cartridge case, reminiscent of the Boer war. In fact, anything which will make a noise that will penetrate to the end of the location. These church bells may not be beautiful or musical, but they have a beautiful calling all the same.

“Ring out the old, ring in the new,

Ring out the ‘false, ring in the true,

Ring in the valiant men and free,

The larger heart, the kindlier hand;

Ring out the darkness of the land,

Ring in the Christ that is to be.”

The people often gather together long before the service commences and dispense the news of the day to one another, or discuss questions of mutual interest. Usually the bell is rung half-an-hour before service as a preliminary warning, and the second bell is rung at service time. However great may be the babel of tongues outside, when once the people are inside their demeanour is marked by reverence and decorum. Even the school children sit quietly in the House of God, and their tongues are never unloosed until the service is over, except to sing.

The stranger would look in vain for any musical instrument to lead the singing. Such are rarely used in any services. The natives have voices of rich sonorous quality, and when they sing one of their native hymns in full lusty tone an organ would have no chance of asserting itself. The tune is struck up by a precentor, who, without the aid of tuning fork is able to pitch the tune at the right key from his tonic sol-fa tune book. All the children are taught to read tonic sol-fa in the schools, and so by this time a large proportion of the congregation can read the music in this notation.

The women have a peculiar flute-like quality in their voices. The men usually sing a deep sonorous base. Comparatively few natives sing tenor, but the few who do make up for their smallness of number by the penetrating power of their tone. Many of the old-fashioned hymns are sung with a verve and vigour which would astonish many of the people at home, and while the great rolling tunes are always the favourites, these people can sing with great expression and devotion some of the sweet and tender hymns. Occasionally during the collection or during the departure of the congregation an anthem will be sung by the choir. In the recent Choir Competition held in connection with our Jubilee, the quality of the singing of some of the choirs came as a revelation to the Europeans who had the privilege of listening. A great many of our best hymns are translated into the native languages – “ Lead kindly light,” “Nearer, my God, to Thee,” “Rock of Ages,” “Abide with me,” “Art thou weary? ” and a host of other familiar hymns are very popular. Solos are seldom heard in church. The natives prefer concerted music, and if the choir is rendering an anthem with which the congregation is familiar it is impossible to keep them all from joining in.

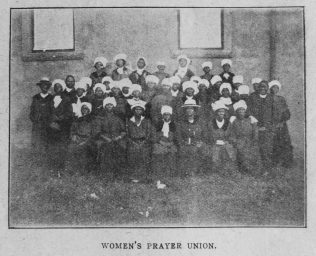

In one corner of the church, usually near to the preacher, will be found a band of women with white docks and red blouses. These are the women of the Prayer Union, and amongst the most devoted helpers in our work. They have their own meetings for prayer. They give special attention to new converts, and will often take long journeys into the country to conduct missions or to stir up decadent churches. The rules of membership are strict, and only those of tried fidelity and unquestionable character are allowed to become members. In every large centre we have such a body of women, and their power and influence in the church is very great. Here we see something of the influence of Christian teaching upon the native. In the heathen state the woman is little more than a beast of burden. She receives very little honour or courtesy from the men, who live a comparatively idle life, while she works in the fields and performs the menial services of the kraal. Under Christian influence woman has received much more consideration, is more kindly treated and, within limits, is allowed a certain amount of liberty and authority in the church. Women Leaders attend the Leaders’ Meetings, although they are seldom found at the Quarterly Meetings, but we have only one case in the Aliwal North Circuit of a woman becoming a preacher. This was the widow of the Rev. W.N. Somngesi, a well-educated and cultured native woman, and a devoted worker in the church, but even her appointment as local preacher was strongly opposed by some of the leading laymen and native ministers. Old customs die slowly, and it will be some time before a native woman will be generally acceptable as a preacher on the plan. Through the agency of these Prayer Unions, however, the women have done a splendid work, and in the meetings organised by themselves they conduct the devotions and often speak with telling power. In times of revival and spiritual awakening these women are most assiduous and untiring in their labours, and give splendid assistance.

In some congregations where the people of many tribes gather together we need to use two or three interpreters, and when the native interpreters know their work well there is very little time lost. The preacher utters a sentence and it is repeated in each language by the various interpreters, but if the preacher is used to the method and the interpreters are good it is not necessary for the preacher to wait until his sentence has passed down the line; he can be going on with his sermon, and the others will carry on, so that the whole thing appears to be more like an unmusical vocal quartette. Some of the interpreters are exceedingly clever, and when they possess the right temperament will often repeat the gestures and intonation of the preacher as well as his mere words.

The great day of the quarter is of course the “Nachtmaal” or Sacrament, when the outside members come in from the farms arrayed in their best robes, and the church is filled with a throng of natives attired in gay colours which no European would wear. On such occasions the candidates for full membership are received. They have already passed an examination before the Leaders, where they repeat the Ten Commandments and the Apostles’ Creed. They also answer questions on faith and doctrine, and make a declaration of their Christian experience. If such have been baptised in infancy they are merely given the right hand of fellowship before the whole congregation, but those who have not been baptised now go through the ceremony. If there are members who have been suspended from membership, and the period of discipline is ended they are received again into full membership, but must make a public confession.

References

Christian Messenger 1921/318

No Comments

Add a comment about this page